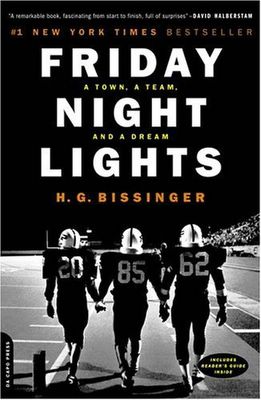

Books: Friday Night Lights

To continue my book review series, today I'll talk about H.G. Bissinger's Friday Night Lights.

This is a story about misplaced passion and unleashed anger in the form of high school football. It is a story that seemingly wanted to be nostalgic, yet something went wrong. Early on, in reading Friday Night Lights, you are made aware that something, sometime, had happened, and that no one had the perspective to see it. The prologue ends with a man in town telling the Odessa Permian Panthers head coach Gary Gaines that "life really wouldn't be worth livin' if you didn't have a high school football team to support."

Win the state championship. That's what people wanted. The economy, which in 1988 was not very good at all, could continue to fall apart. Yet life would be better if the Panthers could just win the state title.

The reader learns very quickly that this is not just a book about football, it's a sociological and historical look at a town that loved it, and the education system that fostered it. It's also a story of family relationships, and the lack of them.

It is also a story of black and white.

Most who met Boobie [the team's running back] agreed that he was one of those kids for whom the game of football had become as important, as indispensable, as a part of their bodies. Taking it away would be like amputating a leg. Some in town, most of them black, worried about what might happen to hm if it somehow didn't work out, what the incredible effect of that absence might be. They saw something potentially dangerous in it all. And some in town, all of them white, gleefully suggested that Boobie Miles, without the ability to carry a football in his hand, might as well get a broom and start preparing for his other destiny in life -- learning how to sweep the corners of storerooms.

On other occasions, some whites offered another suggestion for Boobie's life if he no longer had football: just do to him what a trainer did to a horse that had pulled up lame at the track, just take out a gun and shoot him to put him out of the misery of a life that long longer had any value.

"What would Boobie be without football?" echoed a Permian coach when asked the question one day. The answer was obvious, as clear as night and day, black and white in Odessa, Texas, and he responded without the slightest hesitation.

"A big ol' dumb nigger."

Odessa, Bissinger writes, was a town that did not begin school desegregation until 1982. Yes, 1982, that's not a typo. Racial attitudes were still adjusting to those changes:

"The most amazing thing to me is the shock on people's faces that I'm offended by the word nigger," said Lanita Akins. "They are truly shocked that not only am I shocked, but I have friends who are black."

The white people in town may not want blacks, or Mexicans, living with them or going to school with their children, but if desegregation was going to happen, it would happen on their terms. In order to mix the schools up, the predominately African American high school would be closed, and many of those black kids would be sent to Permian...so black athletes could play football. The Mexican kids, on the other hand, would not. "It was gerrymandering over football," one player would say.

It may seem unusual that children would be considered a commodity, like the oil that caused the county's boom and busts in the first place. Yet it wasn't just the black kids that were treated that way...the entire team was. Winning was more important than their bodies, their education, and their mental health.

"I don't think they realize these are sixteen, seventeen, eighteen-year-old kids," she once said. "I don't think they realize these are coaches. They are men, they are not gods. They don't realize it's a game and they look at them like they're professional football players. They are kids, high school kids, the sons of somebody, and they expect them to be perfect."

As long as they played, they were treated differently:

Gary [Edwards, a player on the competing football team to the Panthers] had found that out during test day in one course. The class started out routinely enough. The teacher passed the tests around the room, and Gary of course got one just like everyone else. But then he got something else that one else got: the answer sheet.

The teacher realized the situation might be confusing for Gary, since exams usually came only with the questions. So he took him out into the hallway just to make sure Gary recognized what it was that had been thrown on his desk.

Later on Edwards ran into a teacher that dared fail him...and that teacher lost his job.

When playing, and playing well, they were legends in the town. Heroes. Supermen.

They trade their bodies for cheers. They live the greatest years of their lives now, in order to dream of them later on.

If you've ever wondered why a guy like Randy Moss acts the way he does, you might learn something of it in this book. If you've ever looked back upon a time in your life as "the best years I've ever had," you will sympathize with the participants in this tale.

You may also ask yourself what Gods you worship? What athletes or politicians? What do you look for to escape your woes, and what are these people sacrificing for you to do it?

Friday Night Lights was not a book received well by the people in Odessa, and I have no idea if the book is accurate or true. What I do know, however, is that this book is a chilling, provocative read.

One well worth picking up.

RELATED LINKS:

Other Book reviews

Friday Night Lights, Ten Years Later

Mojoland: The online home of the Odessa Permian Panthers

Looking back at the movie.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

|<< Home