Are We Living Through The Fall of Modern Rome?

[Sorry for no posts over the past few days, my Internet connection was down.]

New Yorkers are never shy about their city. We consider it, and for the most part our country, as the center of the current world. We are the heirs of Athens, Rome, London, Paris, Constantinople, Baghdad (yes Baghdad, check your history), etc. The previous 100 years was called by many the "American Century," with good cause.

Yet every rise has its fall.

This is what struck me when I read Thomas L. Friedman's article in the New York Times Magazine titled "It's a Flat World, After All". It is summed up in one sentence:

''The playing field is being leveled.''

Technology is "making the world flat," and America's natural protectors of our wealthy way of life, education and geography, are quickly being demolished. This is not a sudden process, but something centuries in the making. Friedman writes:

This has been building for a long time. Globalization 1.0 (1492 to 1800) shrank the world from a size large to a size medium, and the dynamic force in that era was countries globalizing for resources and imperial conquest.

Globalization 2.0 (1800 to 2000) shrank the world from a size medium to a size small, and it was spearheaded by companies globalizing for markets and labor. Globalization 3.0 (which started around 2000) is shrinking the world from a size small to a size tiny and flattening the playing field at the same time. And while the dynamic force in Globalization 1.0 was countries globalizing and the dynamic force in Globalization 2.0 was companies globalizing, the dynamic force in Globalization 3.0 -- the thing that gives it its unique character -- is individuals and small groups globalizing.

Individuals must, and can, now ask: where do I fit into the global competition and opportunities of the day, and how can I, on my own, collaborate with others globally? But Globalization 3.0 not only differs from the previous eras in how it is shrinking and flattening the world and in how it is empowering individuals. It is also different in that Globalization 1.0 and 2.0 were driven primarily by European and American companies and countries. But going forward, this will be less and less true.

Globalization 3.0 is not only going to be driven more by individuals but also by a much more diverse -- non-Western, nonwhite -- group of individuals. In Globalization 3.0, you are going to see every color of the human rainbow take part.

But how did this happen? Did some foreign power force this new economic way on us? Not so, says Friedman. We did it, with the Internet boom, by investing in the very devices that the world may use against us. Friedman writes:

[T]he Netscape stock offering triggered the dot-com boom, which triggered the dot-com bubble, which triggered the massive overinvestment of billions of dollars in fiber-optic telecommunications cable. That overinvestment, by companies like Global Crossing, resulted in the willy-nilly creation of a global undersea-underground fiber network, which in turn drove down the cost of transmitting voices, data and images to practically zero, which in turn accidentally made Boston, Bangalore and Beijing next-door neighbors overnight. In sum, what the Netscape revolution did was bring people-to-people connectivity to a whole new level. Suddenly more people could connect with more other people from more different places in more different ways than ever before. <>No country accidentally benefited more from the Netscape moment than India.

''India had no resources and no infrastructure,'' said Dinakar Singh, one of the most respected hedge-fund managers on Wall Street, whose parents earned doctoral degrees in biochemistry from the University of Delhi before emigrating to America. ''It produced people with quality and by quantity.

But many of them rotted on the docks of India like vegetables. Only a relative few could get on ships and get out. Not anymore, because we built this ocean crosser, called fiber-optic cable. For decades you had to leave India to be a professional. Now you can plug into the world from India. You don't have to go to Yale and go to work for Goldman Sachs.'' India could never have afforded to pay for the bandwidth to connect brainy India with high-tech America, so American shareholders paid for it.

Giving others opportunities certainly fits in with our ideals, but in the past that meant immigrating here. In this new world, that won't be needed.

It didn't require our sacrifice either. When it comes down to cold hard cash, and our homes, our jobs, our PS2s, and our comfort level, it could be devastating to Americans. It means we have to work harder, for less, than we are accustomed to. Friedman puts it this way:

We need to get going immediately. It takes 15 years to train a good engineer, because, ladies and gentlemen, this really is rocket science. So parents, throw away the Game Boy, turn off the television and get your kids to work. There is no sugar-coating this: in a flat world, every individual is going to have to run a little faster if he or she wants to advance his or her standard of living. When I was growing up, my parents used to say to me, ''Tom, finish your dinner -- people in China are starving.'' But after sailing to the edges of the flat world for a year, I am now telling my own daughters, ''Girls, finish your homework -- people in China and India are starving for your jobs.''

I don't think we're up for it. Not right now.

Spastically, liberals will ask to roll back globalization. "Let's pass some laws against NAFTA," or similar comments. This will not do. The gun has been fired, and we will not get our bullets back. To try to do so would be like spitting against the wind.

Conservatives will ignore the matter, saying that this is all a good thing. "The market will take care of itself" they will say...until perhaps it is too late.

Much like our American capitalistic empire today, the Roman Empire had became so widespread and diverse that it stopped being "Roman". It had literally built the roads that led to its destruction.

Have we done so, virtually?

RELATED LINKS:

More Religion, Science, and Philosophy

The Fall of Rome

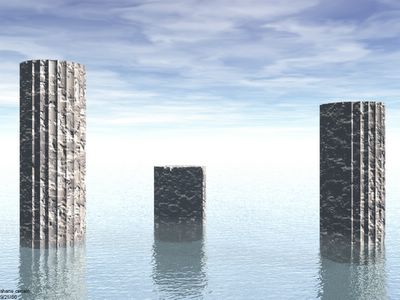

The Fall of Rome Image

WEB STUFF:

One of my old posts on soccer has a great new comment (by anonymous). Check it out here.

Do you hate the Red Sox? Then stop by here.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

|<< Home