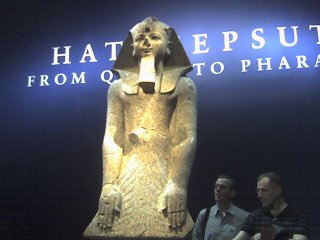

Hatshepsut at New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art

Being back in New York gave me the opportunity to join my Dad at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This time, we focused on the Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh exhibit.

Being back in New York gave me the opportunity to join my Dad at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This time, we focused on the Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh exhibit. The museum Website describes it as:

The museum Website describes it as:Hatshepsut, the great female pharaoh of Egypt’s 18th Dynasty, ruled for two decades—first as regent for, then as co-ruler with, her nephew Thutmose III (ca. 1479–1458 B.C.). During her reign, at the beginning of the New Kingdom, trade relations were being reestablished with western Asia to the east and were extended to the land of Punt far to the south as well as to the Aegean Islands in the north. The prosperity of this time was reflected in the art, which is marked by innovations in sculpture, decorative arts, and such architectural marvels as Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri. In this exhibition, the Metropolitan’s own extensive holdings of objects excavated by the Museum’s Egyptian Expedition in the 1920s and 1930s are supplemented by loans from other American and European museums, as well as by select loans from Cairo.

When you explore Egyptian, you realize that some of our ways date back thousands of years. One example of this is the love of gold and jewelry. This Ring-Bead Necklace dates at around 1550 B.C.

When you explore Egyptian, you realize that some of our ways date back thousands of years. One example of this is the love of gold and jewelry. This Ring-Bead Necklace dates at around 1550 B.C. It all started when Tuthmose I, pictured here (probably), died. Hatshepsut's two brothers had previously died, putting her in an unprecedented position to gain the throne of Egypt. The only male competitor to the throne was Tuthmose I's young son by the commoner Moutnofrit, Tuthmose II, whom this website says she married to become Queen. While he technically became Pharaoh, Hatshepsut seems to have run the territory in his first few years her half brother was in power.

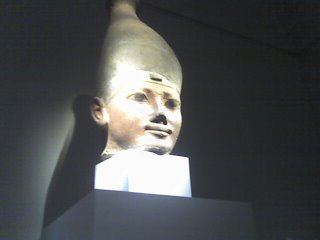

It all started when Tuthmose I, pictured here (probably), died. Hatshepsut's two brothers had previously died, putting her in an unprecedented position to gain the throne of Egypt. The only male competitor to the throne was Tuthmose I's young son by the commoner Moutnofrit, Tuthmose II, whom this website says she married to become Queen. While he technically became Pharaoh, Hatshepsut seems to have run the territory in his first few years her half brother was in power. Here is an image of Tuthmose II, who was too young to take the throne when Tuthmose I died. Within a few years of serving as his regent, Tuthmose II died and Hatshepsut took the throne as her own. It was an usual move for a woman to make. Waiting in the wings, however, was her nephew Tuthmose III. As he grew old enough to rule, he became more and more impatient. Hatshepsut would rule the most powerful and advanced civilization in the world for over 20 years.

Here is an image of Tuthmose II, who was too young to take the throne when Tuthmose I died. Within a few years of serving as his regent, Tuthmose II died and Hatshepsut took the throne as her own. It was an usual move for a woman to make. Waiting in the wings, however, was her nephew Tuthmose III. As he grew old enough to rule, he became more and more impatient. Hatshepsut would rule the most powerful and advanced civilization in the world for over 20 years. Here is a chair dating around 1473 B.C. People were small then.

Here is a chair dating around 1473 B.C. People were small then. When Hatshepsut's reign ended, she was buried with honors. Yet soon after, her name started to be removed from official sites all over Egypt. It seemed to be systematically done, and a long process to be done.

When Hatshepsut's reign ended, she was buried with honors. Yet soon after, her name started to be removed from official sites all over Egypt. It seemed to be systematically done, and a long process to be done.One website has a theory as to why:

But as Tuthmose III grew, her sovereignty grew tenuous. He not only resented his lack of authority, but no doubt harbored only ill will towards his step-mother's consort Senmut. Senmut originally intended to be buried in the tomb he designed for Hatshepsut, but was actually buried nearby in his own tomb. Not long after his death, however, his sarcophagus was completely destroyed. The hard stone that had been carved for his funerary coffin was found in over 1,200 pieces. His mummy was never found. Hatshepsut's mummy was likewise stolen and her tomb destroyed. Only one of the canopic jars was found, the one containing her liver. After her death, it is presumed that Tuthmose III ordered the systematic erasure of her name from any monument she had built, including her temple at Deir-el-Bahri. Since most of the images of her were actually males, it was convenient to simply change the name "Hatshepsut" to "Tuthmose" I, II or III wherever there was a caption. Senmut's name was also removed. Whether Tuthmose killed Hatshepsut, Senmut and Nofrure is questionable but likely. Since he paid little respect to her in death, it is quite possible he paid even less in life.

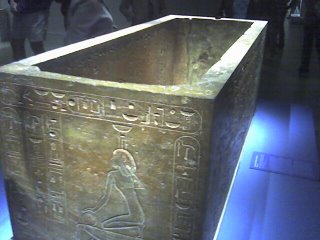

Here, Hatshepsut lied. Until someone moved her, of course. It is a mystery that may never be solved.

Here, Hatshepsut lied. Until someone moved her, of course. It is a mystery that may never be solved.RELATED LINKS:

The story of Hatshepsut

A detailed story of Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut according to Wikipedia

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

|<< Home