Today, my cousins were in from out of town and we went to the

American Museum of Natural History. The museum, located on Central Park West and 79th Street.

NY.com

NY.com describes the place:

For 125 years, the American Museum of Natural History has been one of the world's preeminent science and research institutions, renowned for its collections and exhibitions that illuminate millions of years of the earth's evolution, from the birth of the planet through the present day.

It is an impressive structure, but its collections are hit-and-miss. The museum's strongest suit is an impressive collection of dinosaur bones, which mirrors the

Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh.

The museum knows what it has, as dinosaurs greet you in the main lobby.

Towering high above the crowd is the remains of a

Barosaurus, which can be 88 feet high and (possibly) 88,000 pounds. Further research, however, shows that these are fake bones, made from a cast. Real bones of this type would be too heavy to show in this manner. Regardless of the real-bones versus fake-bones controversy, this is the only Barosaurus on display in the world.

Except it's really not on display.

Oh never mind. Those damned scientists, they are always lying to us.

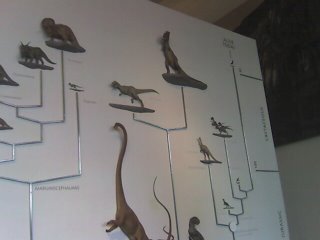

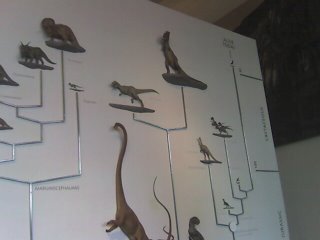

Like any good science museum, the American Museum of Natural History seeks to put things into context, based on the current orthodoxy of scientific beliefs. This graph connects the dots between the species of old and the birds of today. All of the bones on display in the dinosaur section are extinct, yet they are in a very distant manner related to the birds we see in our skies.

This

Edmontonia rugosidens, which is believed to have lived 75 million years ago, is one of the worlds best preserved fossils, as it includes part of the being's scales.

Here is the

Protoceratops andrewsi, which probably lived in Asia (around modern-day Mongolia). They are famous by dinosaur standards, and have popular descendants:

The descendants of Protoceratops andrewsi probably emigrated from Asia to North America where they eventually gave rise to such well known dinosaurs as Triceratops.

The size of the bones are at times larger than life. One example of this is this display of a

Triceratops horridus, which just looks pretty fierce.

High above the capacity crowd is an example of an

Anatotitan copei, otherwise known as a "

giant duck".

Try calling that thing Donald.

But my new favorite dead thing is this

Glyptotherium texanum, which on the Web is described as:

[A] clumsy, heavily armored animal whose body and upper limbs were protected by an immense, turtlelike carapace covered with horny scales. Having a six-foot-long carapace and weighing about a ton, this animal could not have been very balletic! Despite their size, glyptodons thrived in the tropical and subtropical regions of Florida, South Carolina, and Texas. Glyptotherium texanum is sometimes viewed as so highly specialized in its adaptations that local populations could have been wiped out easily by climate change or humans.

He's kind of like an ancient couch potato.

Educational displays, like this description of the location of dinosaur bones, do a great job of putting a pretty nebulous thing to life.

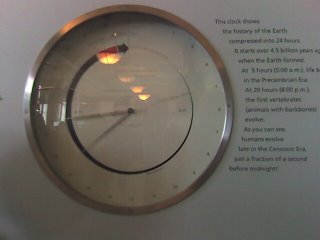

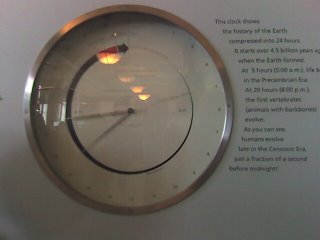

Other displays are somewhat pretentious, like this clock that has humankind as "one second" of the world's existence. What fools, everyone knows the Earth was created in seven days and mankind has dominion over it.

This was the really good stuff.

Here comes some of the bad.

Taking up most of the museum are stuffed dead animals, like this zebra. These displays are educational, showing them by species or by climate type. For instance, this display is called the "Waterhole Group" from Kenya.

Yet for an institution dedicated to science and knowledge of animals, it seemed odd that most of the museum seemed to rely on stuffed, dead (and thus killed) animals.

There is some explanation of this on their

website:

The American Museum of Natural History was established in 1869 in a world very different from today's. Even by the late 19th century, we did not have a firm knowledge of many of Earth's land regions and oceans, the diversity of cultures outside of western societies, and the essential history and organization of life on Earth. Darwin's revolutionary Origin of Species had been published only ten years before. It would be 30 more years before the structure of the atom would be revealed and the laws of heredity disclosed, 40 years before Einstein would share his theories of relativity, and 132 years before the entire three billion nucleotides of the human genome would be mapped.

So it's unlikely that back then the average New Yorker (or American, for that matter), had no idea what the environment of the mountain Nyala group in Ethiopia (above) was like (not that Americans today do either). These stuffed, dead animals were the early interactive displays, and may have predated most zoos.

Nevertheless, the museum itself seems to be a throwback in time and morals, when having stuffed animals around seemed like a perfectly acceptable thing for a liberal society to do. Perhaps, it still is, but I just don't know anyone who has them.

Part of the problem is that the museum itself is just the face of a larger organization. The institution seeks to expand knowledge, with most of the exciting stuff going on

outside of the main view:

The work of scientific research, training, laboratory work, and collections management concern more than 200 scientific personnel, including more than 40 tenure-track curators. The museum's doctoral training program, which connects with five universities (Yale, Cornell, Columbia, and New York universities and the City University of New York), represents the largest and most diversified program of its kind offered by any unaffiliated museum. The collections and research assets are cultivated by continued exploration-over 100 expeditions and field projects annually. A critical resource for the scientific effort is the Museum's Library. With over 400,000 volumes, it is one of the great natural history libraries in the world.

The museum has rooms of fake humans from other cultures wearing clothes. I didn't bother taking pictures of that stuff because I'm not fond of recreations.

Mostly due to its impressive collection, the museum was packed with people. They should have a tourist on display too. We are a strange bunch.

If you like stuffed dead animals, or dinosaur bones, this is the place in New York to find it. The museum also has a space center connected to it, which I have not had a chance to check out yet. Hopefully, in the next few weeks, I'll be able to check it out.

RELATED LINKS:

Other

Things To Do In New YorkOther articles on

Religion, Science, and Philosophy